by Valeri LeBlanc –

Wherever you live—in a large or small city, a village, town or rural area, a dense urban neighborhood or a sprawling suburb—chances are the place you live has a lot of problems. Education problems, problems with crime and public safety, aging infrastructure, declining retail areas, lack of public revenue, traffic congestion, or a myriad of other clusters of problems. And chances are those problems are starting to seem intractable. Once promising solutions may well have been tried and failed.

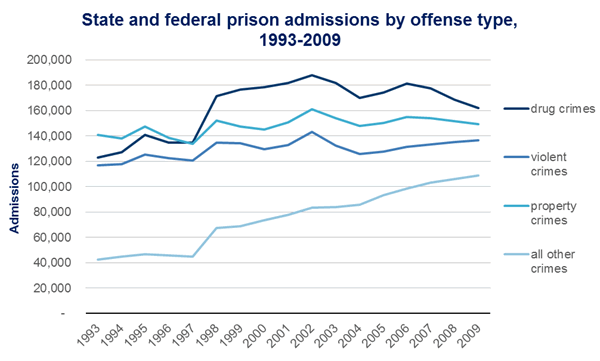

Too much crime? Maybe the underlying problem is drugs, so let’s wage war on drugs—round up a lot of people whose lives are messed up by drugs and put them in jail. But they get out of jail as

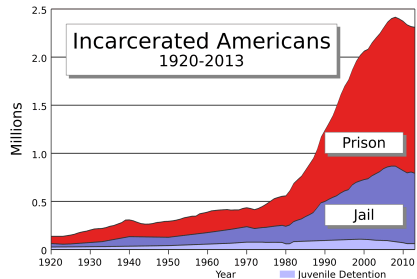

more skillful, confirmed criminals. Jail taught them their craft, and they can’t find a job anyway. Okay, don’t let them out of jail—make sentences longer, and force judges to impose minimum sentences. Whoops, the jails are overcrowded. We have to build more jails. But building and operating all those jails costs a lot of money. Well, let’s privatize the jails, put the genius of the private sector to work.

One solution at a time, the cluster of problems gets worse, and in a  few decades we have become the world’s worst example of a society that locks people up—without justice or equity or benefit. We had better reform our criminal justice system—but perhaps we want to be careful not to make things worse again. It seems at times as if H.L. Mencken’s cynical remark was right: for every problem there is a common-sense solution which is simple, obvious, direct—and wrong. The business writer Peter Senge made it a principle: yesterday’s solutions are today’s problems.

few decades we have become the world’s worst example of a society that locks people up—without justice or equity or benefit. We had better reform our criminal justice system—but perhaps we want to be careful not to make things worse again. It seems at times as if H.L. Mencken’s cynical remark was right: for every problem there is a common-sense solution which is simple, obvious, direct—and wrong. The business writer Peter Senge made it a principle: yesterday’s solutions are today’s problems.

Russell Ackoff, a great thinker at the University of Pennsylvania, decided that business managers and government administrators do not really solve problems at all, and probably should not try. Instead they manage clusters of problems, inter-related, stubborn, even intractable difficulties, not expecting clean, crisp solutions but aiming for overall improvement over time. They steer things in the right direction.

Ackoff thought we needed a name for these clusters of unsolvable problems, and he proposed we call them messes. We manage messes rather than solve problems. This may sound as if it is tantamount to giving up and just muddling along without real direction or purpose—making do and not really trying to improve things decisively.

But what if, instead, it is the way the world really works? What if everything really is intertangled with everything else, and there are no clean, crisp linear solutions? What if improving that dull, lifeless retail district helped improve the education system (quite unexpectedly), and what if there is no way to deal with crime and public safety without working on things that, at first sight, look unrelated? What if things are not just a big mess but are instead a complex system?

Trying to isolate problems and work on them one at a time makes sense to us because we have been doing it successfully, in science, for 500 years or so. The philosopher Rene Decartes proposed it, and it worked: focus in on smaller, singular aspects of things until you can isolate a mechanism by which it seems to work, and then move on to the next thing. Bit by bit, you can make sense of the world and get some control over it. The key word is mechanism. The scientific method treats the world more or less as if it were a huge machine. If you look at a big printing press it looks almost like magic—rolls of paper go in at one end and come out the other as a newspaper or a book. But break it down into cylinders and gears and ink and  pressure plates and it is not a mystery but a complicated machine. The isolated, step by step system made inventing it possible, and makes understanding it possible.

pressure plates and it is not a mystery but a complicated machine. The isolated, step by step system made inventing it possible, and makes understanding it possible.

Enlightenment thinkers, excited by the advances this abstracting, isolating method gave us in understanding and manipulating the world, confidently expected that soon enough social problems would yield to the same inevitable logic. We had some details to work out, sure, but all that would work out in the fullness of time. This belief gave us the social sciences, methods of inquiry into social systems that aimed at the high ground of certainty and clarity.

But what if the expectation of discovering linear, direct knowledge of how social systems work was an illusion from the start, not because social systems cannot be understood at all, but because that’s not how they work, so they can’t be understood that way? What if they are more like organisms than like machines, alive, with all their parts mutually interactive?

As it turns out, even the “hard” sciences have discovered that moving past the mechanical world-view toward a way of seeing things that is interactive, wholistic, organic, and invokes a gestalt rather than a linear diagram, is necessary. It is already happening, especially in biology and physics, and it has to happen in our encounters with social systems.

So dealing with all those problems is not a matter of picking them off one by one. It takes a revolution in how we see and deal with the world. It makes demands on our emotions and our intuitive grasp of things and on our ability to understand complex interactions. Working with those quite different tools, we can steer things in the right direction. Otherwise we will be stuck in the mess we have made.