Even where acrimony now exists it is possible to gain an alignment of the values of people linked to a future picture of the place.

Our deepest assumptions, when we look at places (or just about anything else) favor breaking things down into manageable pieces and solving problems, or understanding processes, one at a time. But if the whole is indeed greater than the sum of its parts, it makes sense for us to start looking at and dealing with the whole place. You can’t solve education problems in the schools, deal with crime in the police department, or get healthy at the doctor’s office. Our boxed-in, linear, mechanistic method no longer produces the results we need. We have gotten where we are by working in silos, but competence that reaches across boundaries is where we need to go now.

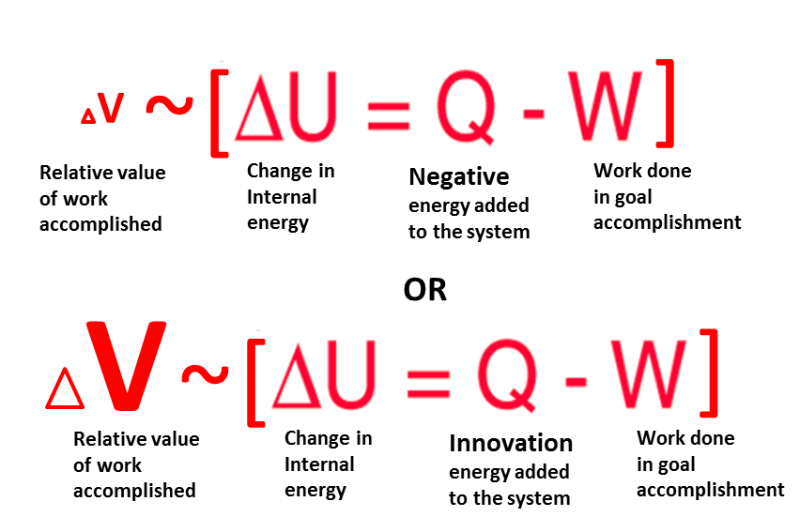

When we try to intervene in a complex system, we will often be changing the energy level in the system. If we are trying to stop something—such as the other guy’s army—we will be trying drain energy from that system. But usually we are trying to get things going, to add energy to a system. People often go straight to money as the way to add energy: hire more people, spend more on promotion, and the like. But there are many ways to add energy that are not based on money: aligning the goals and efforts of different people, tapping into their feelings, building social capital. Generally, whenever we increase participation we increase energy. Systems that originate innovations and insights from a wider base are more resilient; they are less likely to choke up from repetitive thinking.

People have gotten used to the neat categories of thinking in silos. And complex behavior, by contrast, is harder to understand and follow.

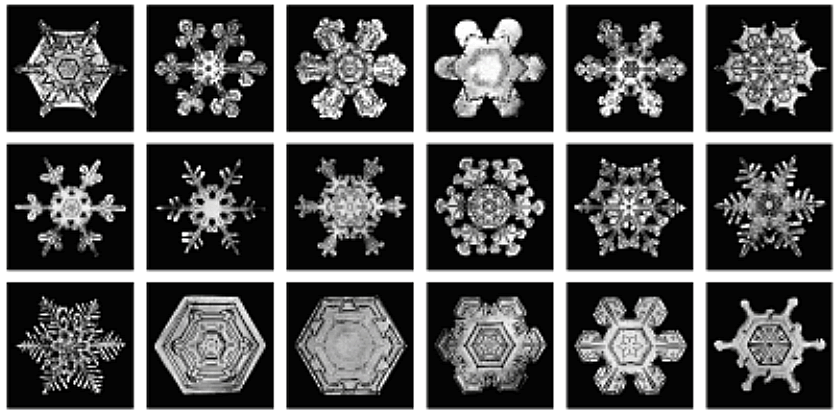

Often, though, complex behavior derives from fairly simple rules. Mathematician-scientist Stephen Wolfram (A New Kind of Science) shows us how, in the world of cellular automata, a few rules of transformation can create complexity (and complex regularity, such as the patterns of zebra stripes or snowflakes) from the simplest of beginnings. Think about a litter of puppies jumping and running around a bowl of milk at feeding time. It looks like a mad scramble, but if you posit one rule—stay close to the milk—it explains itself.

can create complexity (and complex regularity, such as the patterns of zebra stripes or snowflakes) from the simplest of beginnings. Think about a litter of puppies jumping and running around a bowl of milk at feeding time. It looks like a mad scramble, but if you posit one rule—stay close to the milk—it explains itself.

Complexity is about interaction. One puppy moves a bit to the left to get at the bowl of milk, another has to adjust, and the whole brood of puppies begin circling the bowl looking like a pinwheel in action. The good news is that seeming chaos produces resilience in systems. The mad scramble gets things done, and if you can set the right forces scrambling, the system will allow all the puppies to get nourished.

But we almost always look in exactly the other direction to solve problems. We look for leadership: elect a new Mayor and have him or her appoint a new Chief of Police. We look for the lone wolf, for the roaming gunfighter who will step in. Because of the strength of the metaphor of the leader, we cannot see the need for collaboration and broad participation. It’s how our brains work and its called attention blindness.

But without deep participation, we will have excluded groups of people. Often they are affinity groups—they share a bond of some kind. And if they are not part of the process to move forward, they may become obstacles in the path. In the Tremé neighborhood in New Orleans, little progress could be made for years because of racial anger from excluded people who were intimate in creating the many of the great things about New Orleans. Some neighborhood residents, badly hurt by racism and neglect, seemed to want to air grievances and show their rage (even at other black residents they considered race-traitors) more than they wanted to make improvements. The result was to isolate the neighborhood further and delay progress, to no one’s advantage. A lot of human energy was being wasted for the lack of true participation. When a new story of Tremé and its contributions and injustices was written and acknowledged (Love of Place work) it released new energy and made it possible to engage the future. Then with a focused future picture and with a lot of new energy, neighbors could reclaim what matters and build on past achievement working together to create new opportunities.

We can create places that are human, in harmony with nature, and nurture those qualities, which in turn will nurture us. This mutual growth of places and the people in them can be put in place in a system that works, and uses our energy and resources for our benefit. It is very difficult for most of us to have much effect nationally or globally, but almost all of us, understanding complexity and a few simple rules at work in our localities, can improve our places.

____________________________________________

Image captions left to right: Street cars passing, Amish farm, Arizona shop, Austin across Town Lake, In a café